By TU Senan

Part 3 – Struggle For Far Sighted Marxist Position

I was one of the boys in the car that made its way to the Palali airport in the middle of the night. The other is my brother. It’s unimaginable now what must have been going through my aunt’s mind as she sat in the car with us, making our way to Palali airport in the dead of night. My brother and I, just fourteen at the time, couldn’t comprehend the gravity of the situation. We never had the chance to discuss it further with her, as our time together was cut short. Soon after we left the country, despite her illness, Akila threw herself fully into the local administrative work under the control of the LTTE. At times, she worked with Thamilselvan, the leader of LTTE’s political wing, who was killed by the Sri Lankan army in 2007 in a targeted airstrike. Akila also succumbed to her illness, which deteriorated mainly due to the demands of her work, requiring extensive travel across the North.

I have no recollection of what happened at the military controlled Palali airport. Did Akila come all the way or did she leave us in the car for the army to come and take over. We certainly didn’t say goodbye. By that time, the military had grown accustomed to encountering boys with fearful eyes and emaciated bodies. All I can recall is the sight of fully uniformed military personnel directing us to a small room, their amusement evident through giggles and mocking gestures. We were unable to look around or prepare for the journey, and the military, perhaps foreseeing a potential threat, maintained strict surveillance, forbidding any ‘tourism’ around the airport.

With limited resources and unable to speak any language other than Tamil, Colombo wasn’t exactly a welcoming place for us. Key LTTE leaders and negotiators were accommodated in well-known hotels and looked after by the government at the time. But for those fleeing the impending war, our journey was just beginning. As expected, the conflict erupted soon after the withdrawal of the IPKF following the defeat of Rajeev Gandhi in the 1989 election. Having achieved what they wanted, the administration under V P Singh could not justify the continuation of the military presence in Sri Lanka. They faced high costs to maintain their presence not just in terms of resources but also the continuous loss of military personnel as the LTTE began to intensify its guerilla attacks with the help of the Sri Lankan government. The IPKF’s full withdrawal was completed by March 1990. All the paramilitary forces that operated under their protection also vacated along with them. But just before leaving for India, Varadaraja Perumal, then chief minister who was elected with no votes, unilaterally declared Tamil Eelam. This act of desperation won no sympathy for him or the EPRL that he led, as the atrocities that they committed were still very fresh memories for many. This was widely reported at that time and since and has also been the subject of ridicule. Decades later, after the defeat of LTTE in 2009, he surfaced and gave an interview to Indian media that he never declared Eelam or raised the Eelam flag. Instead, he claimed he “hoisted only the Sri Lankan National Flag and the Provincial Flag”!

President Premadasa, whose strategic collaboration was solely aimed at ousting the IPKF, reneged on his agreements with the LTTE. This betrayal ultimately cost him his life, as an LTTE suicide bomber killed him at a May Day rally in 1993.

By the 1990s, as the battle between the LTTE and the Sri Lankan military intensified, the majority of us who had fled to the south had returned to the North, hoping to resume our education. However, a new wave of war swept us back into turmoil, leading us to seek refuge on deserted Delft Island before eventually fleeing to India as refugees. Indian authorities were unable to stem the influx at the time, and while Tamil Nadu offered sympathy and assistance, the conditions in which we were housed were dire. This harsh reality persists to this day, with almost every youngster under constant surveillance or interrogation.

Among those who managed to evade detection were one young man and a woman who meticulously planned a suicide attack on Rajeev Gandhi, the prime minister during the Indian military intervention. Of course they did not do this independently. However the Indian government arrested hundreds who were not linked to this attack, condemning some to life imprisonment. This incident led to heightened discrimination and intimidation against Sri Lankan Tamils by the Indian authorities, driving many to despair and even suicide.

For many of us, the motivation to sacrifice our lives for a cause didn’t stem from political ideology or a clear understanding of social justice. It arose from our lived experiences and the objective conditions we found ourselves in. When faced with a situation where we had nothing left to lose, the drive to make any sacrifice necessary emerged. For many Tamils, joining the LTTE became the only viable option, recruited en masse and further strengthening its military wing. Torture, loss of family members, and persecution drove countless individuals into the LTTE’s fold, a reality that eludes the comprehension of many Colombo and Jaffna liberals and left activists alike.

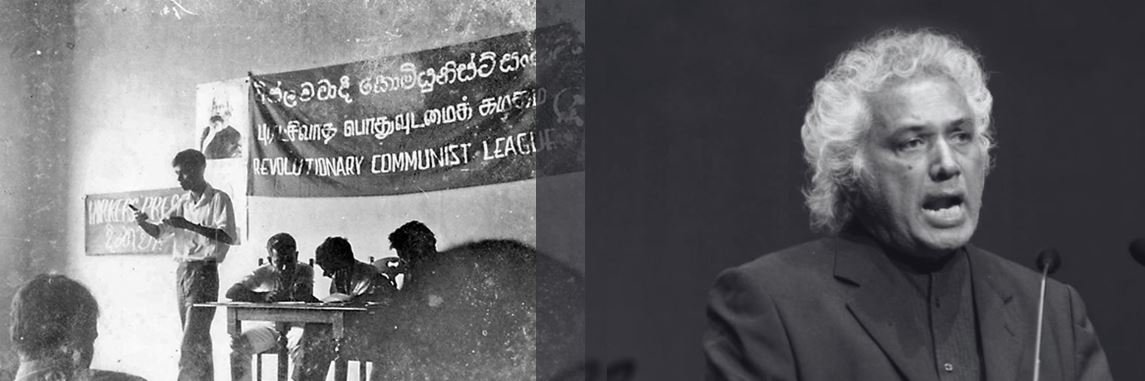

Among the Southern Sama Samajists, there existed a profound misunderstanding of Tamil militants, their motivations, demands, and the nature of the conflicts they were embroiled in. Even the leader of the NSSP at the time, Vikramabahu Karunaratne, was not exempt from this misconception. While many turned to Sri Lankan nationalism to oppose Indian involvement, Bahu took a starkly different path. Unable to formulate a class-based position to counteract nationalism, he instead chose to support India, arguing that it was a more ‘advanced’ secular regime than the chauvinist, religious based JR regime.

The roots of this stance can be traced back to the early 1980s when Tamil militancy surged. Bahu held a deeply confused perspective on nationality, identity, and the Marxist position. In a statement dated 25 November 1983, entitled ‘Letters to a Tamil Sama Samajist,’ Bahu argued that both Tamil and Sinhalese identities were inherently limited, advocating instead for the promotion of an Indian identity. He labelled Prabhakaran, the leader of the LTTE, as a terrorist, demonstrating a lack of understanding of the complexities of the armed clashes involving Tamil militants. Bahu supported his argument by saying that “‘even Uma Maheshwaran has been pushed to the position of rejecting Prabhakaran’s mad terror tactics” (Uma was a leader of another militant group – PLOT – which carried out notorious internal killings), showcasing his misunderstanding of the internal dynamics of Tamil militant groups.

In another letter addressed to the international leadership of the CWI, Bahu advocated for the secession of Tamils from Sri Lanka to join Tamil Nadu, India, under the guise of defending Tamil rights. Tamils should “fight for the unification of the entire Tamil nation within a greater Indian republic”. Such a “united greater India”, he argued, will be a “progressive step”. One conclusion he drew from this is cooperation with Indian forces. He argued: “We cannot hesitate but co-operate with Indian forces on a tactical plane.” “If we are to select between Indira and JR naturally, we will be with Indira who still represents the national industrial bourgeoisie in the sub-continent, whereas JR is simply a comprador Don Juan (not the lecher, the price.).” At the same time, Bahu dismissed the concept of Eelam as an “utterly petit bourgeois” notion, believing it was the role of Sama Samajists to combat such trends.

Bahu’s proposition to join India was an entirely novel demand, which existed only in his brain. It had never existed in Eelam Tamil history, except maybe for a few individuals with ties to Indian intelligence agencies. The distinction between Tamil Nadu Tamils and Eelam Tamils remained a myth to Southern Sama Samajists and liberals alike. However, the most concerning aspect of Bahu’s argument was its complete disregard for the struggles of workers, farmers, and youth in India against their own state, including those of the various national minorities.

In response to Bahu’s position, the International Secretariat issued a lengthy statement, explaining the Marxist stance on the national question and highlighting the Indian bourgeoisie’s historic failure to address this. They pointed out: “The incapacity of Indian bourgeois to solve the national question is demonstrated by the manoeuvres and schemes of Indira Gandhi in Kashmir which had produced a revolt by the Kashmiris. Her incapacity to solve the problems of the population is demonstrated also in Assam which has resulted unfortunately in the Assamese turning on the Bangladeshis and Bengalis who have settled in this area. In the Punjab, there is the problem of the Sikhs which the Indian bourgeois and the Congress have shown themselves utterly incapable of solving. In Maharashtra, the communal violence in Mumbai and the areas surrounding it is an attempt to cause a diversion, at the expense of Muslims, to the movement of the masses in Mumbai, which has witnessed one strike after another by the working class during the last period.”

This statement also pointed out that subordinating all national identities under general ‘human identity’ may be possible following the global socialist revolution, but for now, nationalities will not be prepared to submerge their identity in such an Indian identity. Even in India, Tamils are not willing to do it. The international leadership of the CWI took a clear position of no support to either the Indian or Sri Lankan bourgeois and their political representatives. No pandering to Sinhala chauvinist nationalist propaganda or methods of terrorism. They argued for an independent combat socialist organisation to be built to mobilise the workers, farmers, youth and all oppressed across Sri Lanka, while also standing in support of the Tamil demand for the right to self-determination. The document points out: ‘To be affiliated by the prejudices of the past, not to base oneself upon a Marxist analysis of the present epoch and Marxist understanding of the problem of the national-democratic revolution in colonial countries, and to give a fatal support to so-called ‘progressive’ bourgeois of one country or another would be disastrous course to adopt’.

The international leadership also faced huge challenges in the very same period. Not all members of the leadership had clarity on the national question and fell behind in analysing objectively the developing situation worldwide. In the period of 1987-89, the international leadership was united in opposing the deteriorating abstract position that Bahu was developing. But even then, differences in understanding emerged. Ted Grant, a leading member and seen as the theoretical founder of what was known as the Militant Tendency at that time, argued the impossibility of “setting up of new small nations under modern conditions”. Alan Woods, another leader at that time, blindly followed Ted Grant’s position on the National Question. His intervention in Spain to build the forces of CWI was disastrous in relation to the national questions owing to his lack of understanding on this subject. He argued this position even decades after in a meeting in London during the period of horrific war in 2009. For them, the demand for separate Eelam was abstract as it was “too small”. This came from the view they then had in relation to Scotland and Wales. They argued in the 80s that “the separation of Scotland and Wales from England, for example, would be a catastrophe for the economies of these countries, as well as the struggle for the proletariat for socialism”.

Of course, this position, an echo of the Stalinist position in reality, was not shared by the majority of the leadership. Peter Taaffe, Tony Saunois, Bob Labi, and Clare Doyle, for example, sharply argued against this position. Peter, who had played an absolutely key role in building Militant (now the Socialist Party) into a substantial force in Britain that won a number of victories, including being a catalyst in ousting Margaret Thatcher, disagreed with the wrong position being advanced. These differences came to a sharp collision by late 1989 and early 1990s, when both Ted Grant and Alan Woods took a position denying that the collapse of Stalinism in the Soviet Union led to capitalist restoration. It was only in 2002 that they felt that they could write in a Prospects for World Revolution document that in Russia, “We have to admit that things have not turned out as we expected a few years ago… The movement towards capitalism has lasted for ten years… Ten years is sufficient time to judge. We have to say that the Rubicon has now been passed. The movement towards capitalism has been contradictory, with many crosscurrents, but after every crisis the process has continued with renewed force.”

Peter Taaffe later reflected on the events surrounding the CWI’s World Congress of 1988. He wrote: “We therefore posed tentatively, too tentatively as it turned out, at the CWI’s World Congress of 1988, the possibility of capitalist restoration in Poland and the rest of the Stalinist world. This was before the collapse of the Berlin Wall, but it was quite evident that there was growing opposition to the Stalinist regimes then. Such a possibility was vehemently denied by Grant. In a lead-off on Stalinism in 1988, I ‘set a hare running’ by posing the issue of bourgeois restoration. This caused a certain amount of controversy at the Congress but Grant, as the so-called ‘leading theoretician’, refused to speak. He confided privately that it was because he disagreed with my lead-off but was not prepared to take the floor to answer it.”

Following these events, Ted Grant and Alan Woods’s faction split from the CWI and formed the International Marxist Tendency, which has since evolved into the Revolutionary Communist International. This name better reflects their positions, which are characterized by opportunist and Stalinist tendencies on various issues.

After intense debate on Sri Lanka at a CWI School in July 1985, Bob Labi was tasked with writing a reply to Bahu and his supporters. Recognizing the urgency of the debate, Labi departed the venue early to return to London and prepare the document. However, Ted Grant intervened, preventing Labi from completing the task after he began drafting it. Although the document was eventually edited and supplemented by others, it ultimately lacked clarity on several key issues.

Original article posted on Colombo Telegraph